Aldus: the humanist and the printer

Gutenberg has been overplayed. Do not get me wrong, to Johann Gutenberg corresponds the honor of inventing the process by which a book could be printed, using a movable type. However, to say that he should be credited- as many have said- with the creation of a demand for books and their reading is too far fetched: he responded to an ever increasing demand that existed in that period.

Certainly, by 1455, Gutenberg perfected the process of manufacturing books. From the molds used to make the letters to a sliding box that would guarantee that each letter had exactly the same height as the rest, while accommodating the varying widths of different letters. His method of printing was imaginative and stylish, and it continued as the reigning technology for centuries to come. These accomplishments in themselves make of Gutenberg a well deserved representative of the focus of this Blog: ÂMiddle Ages and beyondÂ. Unfortunately, consumed by debts, he died around 1468.

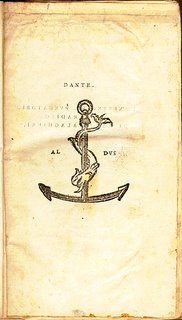

On the other hand, and some twenty years later, Aldus Manutius established a printing business. With monies gifted to him by the princess of Carpi, and shares of the new business venture that he sold to Andrea de Torresani, Aldus started the business. Aldus proposal seemed perfectly fit for Torresani who had bought out previously another printer, Nicolas Jenson, and his Âroman font. Back in those days, the financial success of the printing ventures depended also in those "intangible" assets, such as fonts, typefaces, and the like, and not only in machines, buildings, and so forth. Torresani, a savvy investor, saw the opportunity of using his newly acquired font in Manutius' enterprise.

Considered a humanist scholar by the standards of the times, Aldus decided to publish, firstly, a Greek lexicon, or what we may term today as a Greek-Latin dictionary and phrase book. He was a Greek enthusiast, even designating Greek as the official language of his business:everybody was expected to comply with that requirement, and digressions in other language were not allowed.

Aldus published classics, in Latin and Greek, expanding print runs from 250 to 1,000 which helped him to amortize his costs.

Everything coming out from the Aldine presses was sold out. "Oposculum de Herone et Leandro", "Hypnerotomachia Poliphili" ( a quite stunning and erotic book written by a Dominican monk), Erasmus' "Adagia" ("Collectana Adagiorium", one-liners with genesis and commetary), and works of Petrarch, Virgil, Dante, Horace, Ovid, Thucydides, Plato, and Aristotle, among others, they all were bestsellers in their own right!

With Aldus books became thinner, consequently accessible: he commissioned the creation of new typefaces for books printed in Latin, narrower than the "roman" type and a little more skewed in order to resemble the cursive style. The lowercase letters were of the same height, and they were combined with the small capitals employed in previous Latin editions. These improvements implied that more words were able to fit on one page, which resulted in a book half the size of anything known before and not much thicker. This process is what is known as the Aldine octavos, that is increasing the number of times a "folio" was folded, which it was translated into printed pages, that is the more it was folded , it meant more printed pages, thus the greater the number, the smaller the size of the book.

Aldus' octavos may be compared to Gates' Microsoft: Aldus dramatically changed the way people got involved in the revolutionary transformation of Western culture.

Manutius initiated in that little printing business in Venice the sixteenth century's super- information highway: more information was available to a single individual than it has been available in the past to many institutions.

Those were times were if you had something to say you could just publish it. More books represented more knowledge, and whether your point of view was radical, controversial, revolutionary, sacrilegious, or just contrary to accepted beliefs, so be it.

Aldus should be well remembered. Today, where another revolution in, and through, the internet took place, the blogosphere, where we appreciate the power - and struggle thereof- of the ideas taking place in a new marketplace, a global marketplace, we should reckon Manutius as the forefather of that struggle..

Reference

Boorstin, D. (1983). The Discoverers. New York: Random House.

Durant, W. & A. (1957). The story of civilization. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Grendler, P. (1984). Aldus Manutius: Humanist, teacher, and printer. Providence: John Carter Brown Library.

Hale, J. (1994). The civilization of Europe in the Renaissance. New York: Atheneum.

Lowry, M. (1979). The world of Aldus Manutius: Business and sholarship in Renaissance Venice. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Winship, G. P. (1940). Printing in the Fifteenth Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.